A Glimpse of Stocking

Click image to enlarge

In recent summers, my father has come to Manhattan so we can dine at the bar of the Union Square Café, go to a show, and wrap it up with a nightcap. This year, he suggested we see Anything Goes, the Cole Porter revival currently playing on Broadway. It was a reunion of sorts.

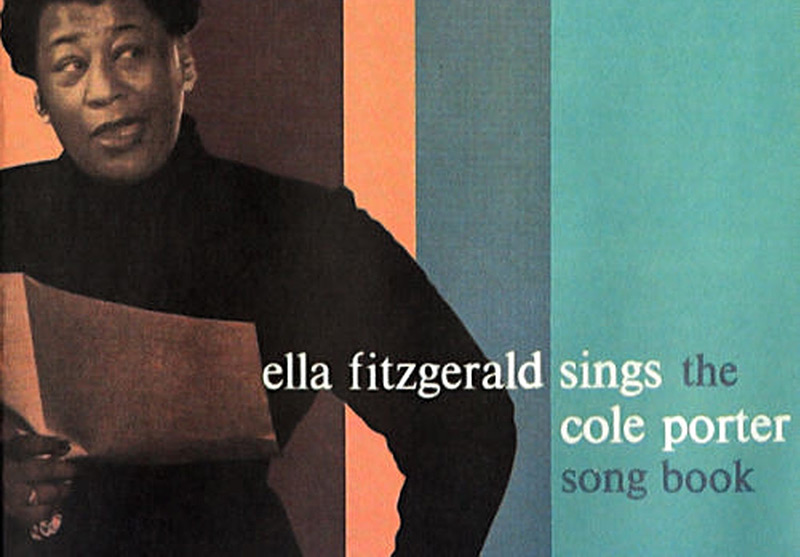

When I was ten, our babysitter Mary Fallon turned on the rarely used kitchen radio to a rock & roll station, and it was never turned off again. Bob Dylan and Bob Seger; Jimmy Hendrix and Jimmy Page; Keith Richards and Keith Moon: in my teens, I came to know all of these gentlemen quite well, and they have been close friends ever since. But before all of that fine electric guitar and amplified attitude, there was Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Songbook (Verve, 1956).

My parents were not particularly musical. Neither played an instrument, neither sang out loud, and neither listened to the radio with frequency. The record collection in the living room was only about two feet long – and that included four inches of Neil Diamond and Herb Alpert. But the double vinyl Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Songbook was one of my father’s favorites and he played it often. As far as I was concerned, he could have played it all night long. Because it had struck a chord with me—and quickly became the first album that I knew end-to-end.

To a bookish boy in a Boston suburb in the mid-1970s, the lyrics of Cole Porter came as something of a revelation. The world I inhabited was relatively carefree; but it was also homogeneous, socially constrained, and politically benign (with parental votes for Nixon and McGovern efficiently cancelling each other out). Outside, there was a lawn to be mowed, leaves to be raked, snow to be shoveled. Inside, there were appliances made by Amana, Frigidaire, and Zenith; and kitchen cabinets stocked with Wheaties™, Hamburger Helper™ and Aunt Jemima’s™ pancake mix. But in our appropriately staid living room—where we housed all of our upholstered furniture—on holidays and Saturday nights, we heard the likes of “Anything Goes,” “Too Darn Hot,” and “Let’s Do It.” It was certainly a plus that these songs featured illicit behavior, but it was the lyrical imagery that ultimately had its greatest influence over me.

For somehow, in the span of thirty-two songs, Cole Porter had fashioned a travel guide to a distant, unnamed and here-to-for unimagined Metropolis. His was an urbane and sophisticated capital, where one’s budget was unlimited, the hour was eternally twilight, and the sights to be seen included all things delightful, delicious and delovely. In his offhand manner, Porter was revealing that somewhere out there was a place where “old hymns” rhymed with “bare limbs” and where all young men and women were knowing, wry, blasé and bold. In short, Porter’s lyrical Baedekermapped out a world even more intriguingly different from mine than The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau (NBC 1974).

Naturally, like all youthful “discoveries”, this one had an element of self-confirmation (adolescent alienation being that feeling which immediately precedes the unanticipated encounter with spiritual kin.) In the suburbs, the edge which varsity athletes had with the ladies, seemed an irrefutable and universal law of nature. But in Cole Porter’s Metropolis, erudite references were apparently used casually in the service of romance. There, one successfully wooed by comparing a girl to the Coliseum, the Louvre Museum, a Bendel’s bonnet, and a Shakespeare sonnet—two couplets that encompass architecture, painting, fashion and poetry in Rome, Paris, Manhattan and London!

For a young, uninformed listener, Porter’s lyrics weren’t emblematic of an era, or a specific locale; they were emblematic of a sensibility. Thanks to that record, I loved the wee hours long before I was allowed to stay up until ten; and I loved Paris in the springtime, long before I knew who, what or where Paris was.

§

If Porter’s lyrics were my introduction to urban sophistication, then the voice of Ella Fitzgerald was my introduction to an equally foreign and alluring world—that of jazz.

The entire project of the various Ella Fitzgerald songbooks (for Porter, Ellington, Berlin, the Gershwins…) was created by Norman Granz to bring Fitzgerald’s jazz inflections to a broader audience. In that service, many of the songs aim to please with smooth vocals backed by sentimental strings. But in others, the horn and rhythm sections support Fitzgerald’s styling in a manner that is decidedly swing. Even to the uninitiated, these songs begin to suggest a smoky netherworld that is also part of Porter’s Metropolis, if on the other side of town.

As with most great vocalists, you sense that Fitzgerald is not simply drawing on technical skill, but on a breadth of experience and a depth of feeling, which can only be found outside the walls of the academy. The manner in which she brings these experiences and feelings to Porter’s songs is at the heart of jazz interpretation – and it is an enticement for young listeners to go in pursuit of their own experiences. While Fitzgerald’s singing of Cole Porter may not represent the most adventurous of jazz interpretations, she was taking me one step closer to the furnace; and from there, it was a hop, skip and a jump to Billie Holliday, Miles Davis and John Coltrane – those inner circles where earthly bounds are briefly shed through some magical combination of passion, honesty and competence—at two in the morning before an audience of loners and aficionados.

You may accuse me of over-glamorizing jazz, or the artistic position of an African American woman in the 1950s. But, in a way, that’s my point. Like a Depression era American watching a Fred Astaire film, I was prepared to take the whole folly at face value. At the time, I wouldn’t even have accepted the compound “over-glamorizing” into my vocabulary, as it was so plainly a contradiction in terms.

At any rate, I suppose the moral of the story is that you should keep a close eye on what your adolescent children memorize – it’s your window on the dreams which will probably influence their actions for decades to come.

§

If, through these four sides of vinyl, I was receiving an urbane sensibility from Porter and a will for experience from Fitzgerald, I was also receiving a lasting gift from my father. Because his love of the album was as wistful as mine. He was (is) accomplished, respected, on firm social ground. But in the off-hours, his thoughts too turned towards the Porter/Fitzgerald Metropolis.

Around that time, he and I began going to double features in Cambridge. On more than one Saturday afternoon, we sat through back-to-back Bogart. Casablanca and The Maltese Falcon. Key Largo and The Big Sleep. It was the same wistful dynamic at work. Hardened, remote, mysterious, Bogart in many ways represented a persona antithetical to Porter’s smooth, erudite glamour; but for my father, Bogart was just another version of urban style. That in the midst of the 1970s, my father still enjoyed losing himself for the afternoon at Rick’s Café Americain, was an unspoken confirmation that an enviable world lay somewhere else. So over the years, even though my father’s practical suburban self has inevitably encouraged me to pursue conventional aspirations, he had already tipped his hand: secretly, I knew that a part of him was hoping I just pursued my dreams.

Amor Towles

The Porter/Fitzgerald Metropolis

August 2011

An abbreviated version of this essay originally appeared on Oprah.com.