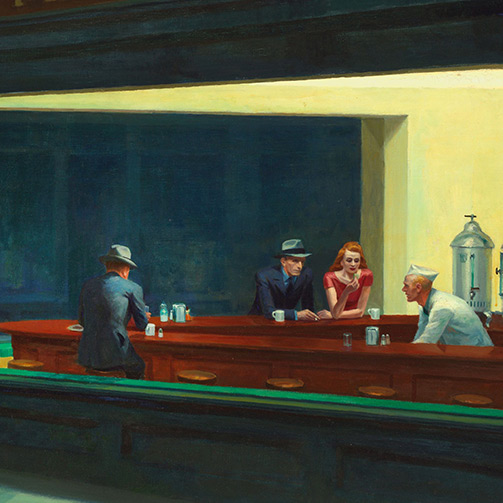

NIGHTHAWKS

Click image to enlarge

Set in Manhattan in 1938, Rules of Civility is told from the perspective of a bright, young woman of limited means for whom a chance encounter in a jazz club leads indirectly to a series of life changes. There are a number of influences which inform the mood and themes of the book, including overt ones like jazz and the photography of Walker Evans, but among the more understated influences are the paintings of Edward Hopper.

Though Hopper was active as a painter in New York between the wars—a crowded, volatile and bustling time for the great metropolis—he opted to become a master of the peripheral reverie and the intimate aside. In a quiet café, a young woman sits by herself at a small marble topped table. As a movie plays for patrons, an usherette leans against a wall out of view of the feature. And as the first members of a well-dressed audience assemble, a solitary woman examines her program in her box.

Characterized by lone figures with downward gazes, subdued moments, muted colors and sharply angled shadows, these paintings are compositionally melancholy. But we do not walk away from them with a sense of alienation or fatalism or some other fine Sartreian sentiment. Rather, we walk away satisfied. For while Hopper’s paintings may be melancholy, they are melancholy in a paradoxically uplifting way.

Take the case of “Nighthawks,” which Hopper painted in 1942. On the surface, this painting of a late hour in a diner could be a textbook depiction of urban loneliness. The four figures seem only modestly engaged with each other. A man with his back to us—his profile shadowed by a fedora—stares silently into his coffee. A woman in red gazes distractedly at her fingernails as her companion listens without expression to the counterman. Like the empty chairs in each of the three paintings shown above, here six empty stools serve as ghostly reminders of those who are otherwise engaged. And, as in so many of Hopper’s Manhattan street scenes, the storefronts opposite the diner look abandoned, the apartments uninhabited. The shadows and the cool colors of the palette—maroon and aquamarine—simply reinforce the almost mournful mood.

But at the same time, there are countervailing forces at work. First and foremost, these paintings of urban isolation fend off melancholy because they are set in the city. This is important as it changes the underlying tenor of the scenes. For Manhattan is generally categorized by noise, crowds, and pace. So, these subdued moments in sparse, uncrowded corners represent an escape for the central figures. These are the particular locations and the precise times of day when the working girl, the elegant woman and the usherette can find a moment’s repose, when they have the freedom to reflect undisturbed. Perhaps predictably, these four idles come at some point between twilight and the wee hours, when most of the day’s work is done, and the traffic has subsided, and the challenges of the morning have yet to make themselves known.

By offering these glimpses into urban serenity, Hopper’s paintings show that the sprawling metropolis can be possessed by the lone individual. The table near the window and late night counter, like the stoop at dusk and the park bench in the rain, are spaces within the city which can be claimed as one’s own and from which the world recedes—allowing one’s thoughts to dwell on the most personal of matters: memories and dreams and regrets. The very framing of the paintings has been carefully calibrated by Hopper so that the figures are not overwhelmed by their surroundings. And they are positioned just close enough to us that were we to say “Excuse me…” they might well look up from their reveries to see if it is to them whom we speak.

Our impression that these four spots are welcome retreats is enhanced by their evident accessibility. These are not the finely furnished sitting rooms of the Fifth Avenue townhouses or the leather bound libraries of the private clubs. These are not environments defined by exclusivity, pretention or decorum. The theater, the cinema, the diner—these are quasi-public spaces, which by-and-large welcome the city’s denizens regardless of race or social class. Warmth, light, and unrushed reflection are offered to all of us for the democratic price of a cup of coffee.

What’s more, these places are surprisingly accessible across time. Hopper has chosen environments so essential to urban living, and has stripped them so systematically of clutter that they are as much of our time as they were of his. Some might casually attribute the popularity of these paintings to nostalgia, but that is exactly wrong. For New Yorkers can and do retire to these four corners today, pausing in the same ambience at the same hours for the same reasons—despite the passage of a world war, an atomic bomb, and a moon shot.

But ultimately, I think these paintings fend off fatalism, because we recognize the settings as those where lives can change unexpectedly. The majority of our waking hours are shaped by formal constraints. Our careers and social circles—the two forces that dominate our waking lives—are essential and fulfilling; but they are also inhibiting. Whether we are seated at a table in a conference room among our colleagues or in a dining room among friends, our interactions will be prescribed by habits, expectations, and rules of conformity. In as much as we play a part in life, these purposeful assemblies are where the part is played. Hopper tends to steer clear of cloistered environments showing preference for those that are more open, anonymous, and thus exposed to chance.

Were we, while walking aimlessly in the hours after dusk, to suddenly enter this well-lit diner and sit on one of the six empty stools, we could eventually strike up a conversation with any or all of our fellow nighthawks. And they would have no expectations for how we might act (sentimental or brazen or shy); they would have no preconceptions of our inclinations (towards business or sports or the arts); no vested interest in our opinions or style. As a result, the diner and the cinema and the café are places where conversation can lead quite quickly to odes and laments and confidences. And that is why they are the places where the spur of the moment and love at first sight prefer to dwell.

Amor Towles

New York

July 2011

This essay originally appeared as a blog for barnesandnoble.com

Nighthawks (1942) by Edward Hopper is (as of writing) viewable at The Art Institute of Chicago.