Lincoln Highway History

Carl Fisher and the Lincoln Highway

In the 1920s, the number of automobiles in the United States grew more than fifteen-fold from 500,000 to eight million, but traveling by car was by no means easy. At the beginning of the decade, there were more than two million miles of road in America, but less than 10% of them were paved such that many of them became unpassable following heavy rains. In addition, the majority of roads spider-webbed out of town centers toward local residences and farms. There were few roads that had been designed to directly connect municipalities or cross states, and none of them had identifying signs. The combination of these factors made long distance car travel more of an expedition than a pleasure. But in 1912, an American entrepreneur named Carl Fisher set out to change all of that.

Born in the Indianapolis area in 1874, Carl Fisher was a classic American success story. Fisher’s father abandoned the family when Fisher was boy, so at the age of twelve Fisher dropped out of school in order to start making money. In the years that followed he held a variety of jobs including selling newspapers, tobacco and candy on the trains about to leave Indianapolis’s Union Station. A bicycle enthusiast, Fisher opened a bicycle repair shop with his brother when he was seventeen. This led to an interest in cars, car racing, and car manufacturing. In 1904, when Fisher was thirty, he and a partner bought an interest in a patent for a new type of automotive lamp. Within the decade, nearly every car made in America had Fisher’s Prest-O-Lite headlamp and Fisher was a rich man.

As a car racing enthusiast (who held several land speed records), in 1909 Fisher joined with several partners to establish the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. In 1911, after Fisher had the raceway paved, 80,000 people gathered there to watch the race that he had established: the Indie 500.

Around this time, Fisher went on a vacation to Miami, Florida. While there, he visited the swampy, bug-infested barrier island that separated the city of Miami from the Atlantic Ocean. Upon seeing it, Fisher immediately recognized that with the right infrastructure it could become the perfect vacation destination. After buying up land in 1912, dredging part of Biscayne Bay, and financing the completion of a bridge connecting the barrier island to the mainland, Fisher built several luxury hotels on the island including the Flamingo, launching what was to become Miami Beach.

As he traveled, Fisher became acutely aware of the poor condition of America’s roads. In 1912, he had a vision of a paved highway that crossed the country. From the beginning, he saw such a road not simply as a means of improving commerce, but of providing Americans with the opportunity to travel their great country as tourists from sea to shining sea. This was at a time before the federal government had taken an interest in the nation’s roads. So, Fisher established The Lincoln Highway Association to fund the project independently. Ever the entrepreneur and promoter, he drummed up national publicity for the project, then solicited donations from the CEOs of leading automotive companies like Goodyear and Packard, from national figures like Thomas Edison and Teddy Roosevelt, and ultimately from the general public. With this private financing in place, the Association went about connecting the east and west coasts of America by means of a single paved route.

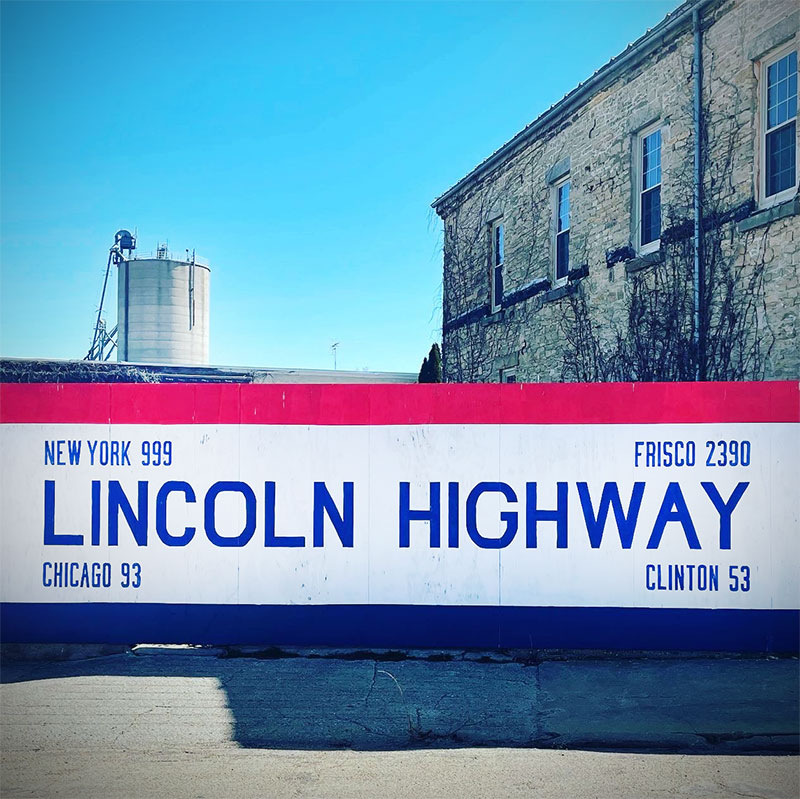

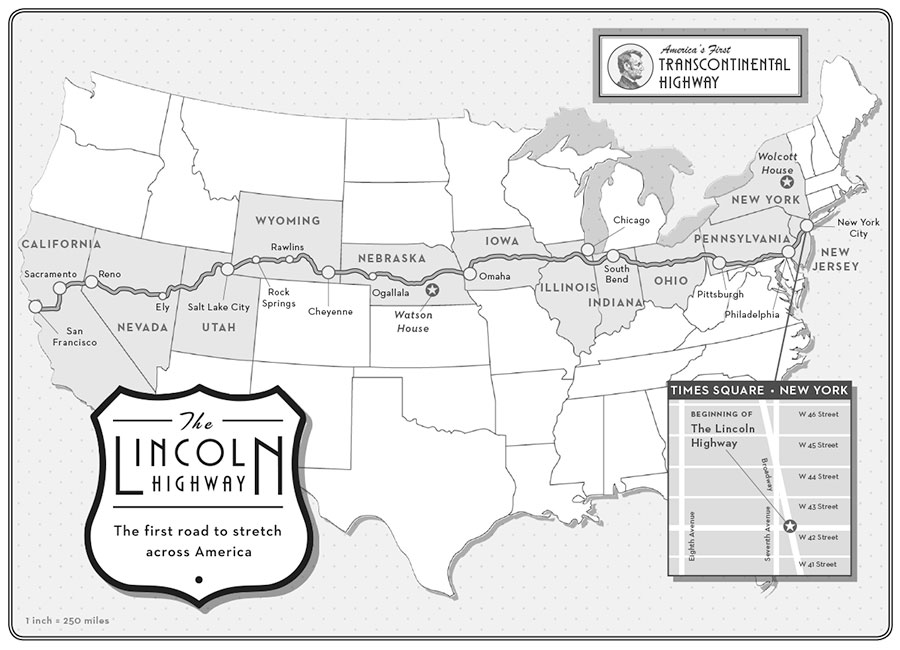

Beginning in New York City’s Times Square and ending at the Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco’s Lincoln Park, the Lincoln Highway was practically a straight line, passing through twelve of the forty-eight contiguous states. Within a matter of years, it was the most famous road in America. Before the Lincoln Highway was created, a transcontinental crossing would take about sixty days. As there were few services in between towns, those who sought to cross the country needed to carry fuel, tools, tents, food and water. In 1913, there were only 150 trips across the continent by car. With the creation of the Lincoln Highway, the crossing could easily be done in twenty days. In fact, in 1916, the race car driver, Bobby Hammond, made the trip in six days and ten hours. In addition, hotels, gas stations and restaurants were popping up along the route. By 1923, 20,000 Americans would make the crossing in a year.

Like many innovations, the Lincoln Highway “paved the way” to its own demise. Recognizing the success of Fisher’s creation, in the 1920s the Federal government began helping finance, organize, and oversee the nation’s highways. In 1926, the government established the numbered route system, taking over many legs of the Lincoln Highway in the process. But the real death knell of the Lincoln Highway was sounded within five years of its opening…

In the summer of 1919, less than a year after the conclusion of the First World War, the US Army sent a highly-publicized convoy across the country to showcase our military strength and to bring attention to the necessity of maintaining a well-funded and capable national defense. Starting at the Ellipse just south of the Whitehouse in Washington, DC the convoy quickly joined up with the Lincoln Highway and used it to cross the country. The convoy was made up of about eighty vehicles including heavy duty trucks, fuel tankers, artillery tractors, an aerial search light truck, armed reconnaissance cars, ambulances, and motor cycles collectively manned by thirty-five officers and 260 enlisted men. The crossing, however, proved something of a fiasco as the uneven quality of the Lincoln Highway and its narrowness made for slow progress given the army’s heavy equipment. As it happened, one of the thirty-five officers on this long, frustrating journey was Lt. Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower. His memories of the saga were very much in mind when as president in 1956, he championed the creation of the Interstate Highway System—the highspeed multilane roads that would crisscross the nation, making the Lincoln Highway obsolete.

Can one still cross the country by means of the Lincoln Highway? Absolutely—as long as one isn’t in a rush. Much of the Lincoln Highway seems more like a country road than what we’ve come to think of as a highway. As a result, it offers an attractive antidote to the interstate system, leading one along a slightly winding path through beautiful open countryside and many smaller American towns.

And what happened to Carl Fisher? Having made a fortune of about $75 million—the equivalent of a billion dollars today—the Florida hurricane of 1926 and the stock market crash of 1929 left him virtually penniless. When Fisher died in 1939 at the age of 65, he reportedly lived alone in a cottage on Miami Beach.